Margaret Leonard on racial equality:

When I was 12 or 13 years old, in the early 1950s, we had a family friend who had moved away from Macon and traveled around the world, becoming sophisticated enough to say anything, even very shocking things. He would come back in the summer to Georgia with his family and rent a house at St. Simons Island, where there were no blacks except servants, and servants were not allowed to swim in the ocean because the ocean was for us, the white people.

One summer my mother and my sister and I stayed a week with them at their rented house on the beach. Our friends had brought a bearer from India, an Indian man who was very dark, clearly not white. One day we drove over to Jekyll Island, which was undeveloped then, and found an empty beach where the bearer could swim in the ocean and not get caught. We swam there too, and I was aware that we were doing something dangerous. If somebody saw us swimming in the same ocean with a black person, we would all be in serious trouble. They would hurt the bearer and arrest us.

But nobody saw us, and later our world traveler friend explained his solution to the race problem. Somebody should lock us all up in a bedroom together (two at a time, I guess) and in a generation or two, there would be only one race, a mix. That was an amazing, shocking thing for anybody to say and I loved it. Of course, I knew, it would never happen. I didn’t realize then that it was already well launched. I didn’t know until a few years later that most of the people we thought were black were the mix, all shades.

For the rest of the ’50s, I listened to people warning us against miscegenation, the terrible doom that would come if we integrated. I usually argued that nobody had anything like that in mind; all we in the movement wanted was equality, fair treatment, an equal chance at education, jobs, food, housing, the vote and the ocean.

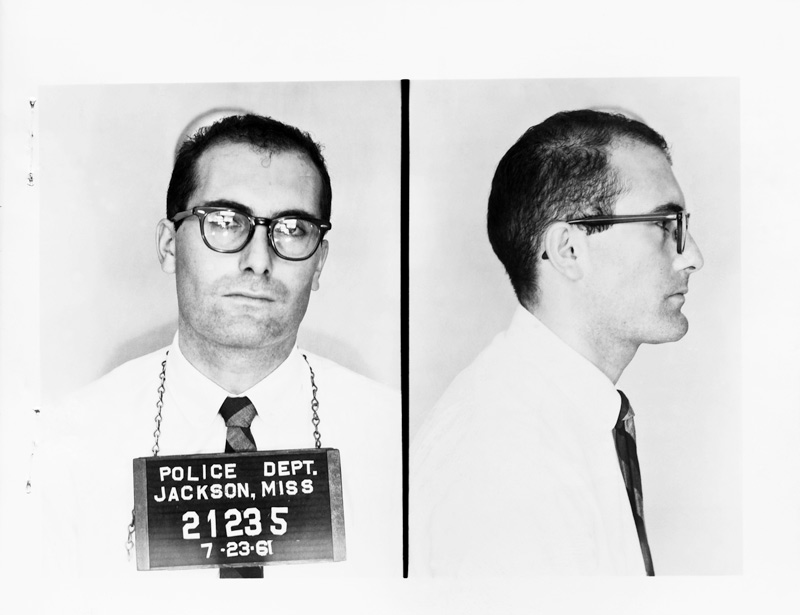

Alex Weiss on joining CORE:

I grew up in the Fillmore District, which was like the Harlem of San Francisco, but at the time it was fairly mixed. It was primarily black, but with lots of refugees. There was a little Jewish section with Jewish delis and Jewish poultry areas and so on, and I went to school with, you know, black buddies. After high school, I joined the Navy, two years active duty, from ‘55 to ‘57, and I had a lot of black shipmates who were friends.

When the Freedom Riders were attacked in Alabama, I was outraged. I just couldn’t believe it. And one of my motivations for joining CORE [the Congress of Racial Equality] and volunteering to go on the Freedom Rides was that I did not want to be one of those good Germans who just looked the other way.

I remember reading in the papers about the Anniston bus burning and that CORE was looking for Freedom Riders. So one day I went down to the CORE office in San Francisco and said, “I’d like to join,” and volunteered to go on the Rides.

I told my father. He was totally against it: “You’re gonna get killed. It’s not us this time. It’s the schvartzes.”

I said, “Hey, you know, this is what happened to you. I’m not gonna stand by.”

That whole idea — if you see evil and do nothing about it you are a participant in it — I really believed that.

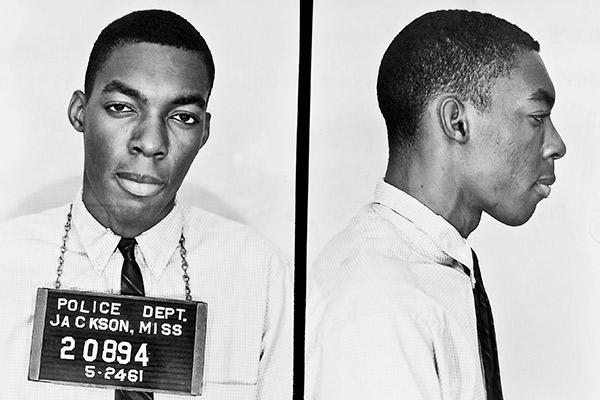

Hank Thomas on joining the Freedom Rides:

My roommate John Moody had been accepted as a Freedom Rider, and at the last minute, he couldn’t go. I don’t know whether it was for illness on his part or some illness in his family. It was too late for them to start interviewing around for someone else, and he suggested, “Well, why don’t you take my roommate?” They looked at my age, and they wanted somebody 21 or over. When I went to see them, I’m a big tall fella so I looked big for my age. But I still say that they just didn’t have time to talk to anyone else so that’s how I got selected.

I always wanted to go where the action was. That’s what happens when you’re 19. You don’t think too much about what the consequences gonna be.

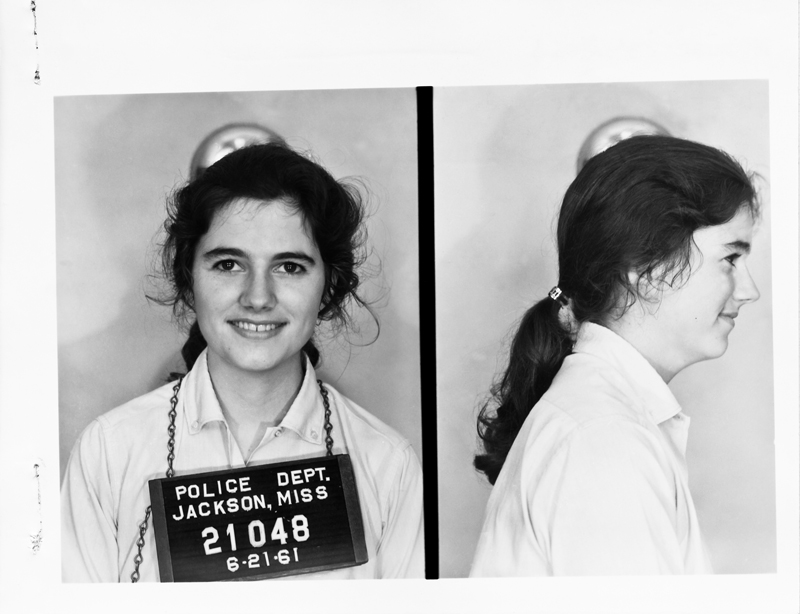

Mimi Real on spending time in Alabama:

We all gathered at the Montgomery [Alabama] bus station [on June 21]. There was some more excitement at the station because, of course, everybody knew who we were, and there was much scurrying around of law enforcement people. The first thing we learned was that there had been a bomb scare on the bus that we were supposed to get on. So the police had to come in and search the bus. And, of course, there wasn’t anything on the bus.

Then the other thing that happened – I can’t remember what order these things happened – is the bus driver, whose shift that was, showed up, realized what he was gonna be doing, and promptly turned around and went home. So there was additional delay, while they rounded up another driver.

Then we all got on the bus. The bus driver kept insisting that the whites all sit in the front and the blacks sit in the back. We refused and all sat in the back. This was a milk-run — the bus stopped at every little cow town in Alabama and Mississippi. The poor bus driver, I guess he figured he was stuck with us, but he sure wasn’t gonna get in any trouble. So he made it quite clear that we were not allowed to get off the bus.

We couldn’t go to the restroom. We couldn’t buy anything to eat. But we were fine with that. But then, in one of the many stops in the middle of nowhere, a lovely black man, probably in his 20s or early 30s, got on, and he had this huge picnic basket of food.

His mother or whoever he had just been visiting had packed it for him, knowing that he probably wasn’t gonna be able to go into any of these little bus stops along the way, and had packed him enough food to feed an army. And he got to chatting with us, and when he learned that we hadn’t anything to eat, he insisted on giving us his entire picnic basket.

So we feasted on fried chicken and all kinds of stuff. And included in this feast was a chocolate layer cake in this big cake box. We ate everything else, but we decided to save the cake. And I was somehow given the responsibility of holding onto the cake. Other than that, the bus ride was totally uneventful.

There was no crowd at all when we arrived at the Trailways station [in Jackson]. The police were there and it was almost perfunctory. As we drove past the front of the bus station, we saw that there was a paddy wagon, a Black Maria, sitting in front. The bus driver insisted that everybody get off the bus first before we got off. Then we got off, and we all filed into the white-only waiting room. The police were waiting for us. The whole thing was very engineered. There weren’t supposed to be any surprises.

We went through this little song-and-dance routine. They asked us to move on. We didn’t. And they said that two or three times, and said they’d have to arrest us if we didn’t move, and we didn’t move. So they put us all under arrest. We had come in the back door of the waiting room, and then we just walked out the front door right into the paddy wagon, me still clutching the cake. I still had that cake with me when I got to the Hinds County Jail, where we ate it.

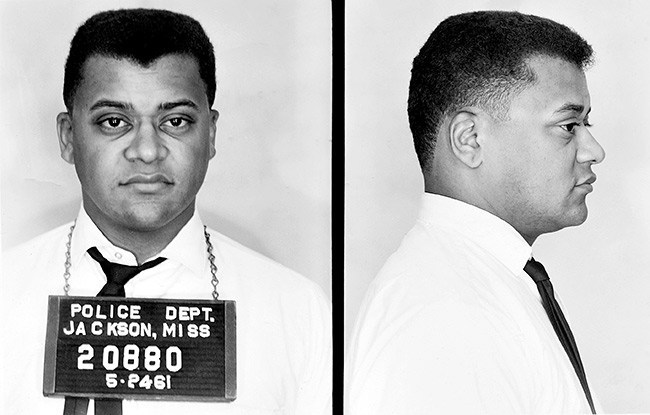

James Lawson on continuing the Freedom Rides:

The role that the movement in Nashville played in the Freedom Rides has not been understood or credited for its strength and creativity. All of us in Nashville knew that John [Lewis] was on the freedom ride. And we saw him in many ways as our national representative in that ride. When the bus burning took place in Anniston, Alabama, we of course were keenly aware of it; and then when the bus ride went on into Birmingham and again met the white mob, we were acutely engaged.

And when the decision was made by the riders, basically because of movement injury and exhaustion, that they would catch a plane in Birmingham and go on to New Orleans and not go by bus any further. We understood the foundation of that decision; we understood the personal pain in that decision but we also understood something else, and that for us was important.

Our work in nonviolence in Nashville caused a number of people to say, spontaneously and apart from one another, “We cannot allow the freedom ride to be stopped by the violence of our opponents.” The Central Committee [as the group that ran the Nashville Student Movement was known] met the better part of the night — some people say it was SNCC; well, at that stage of the game, it wasn’t SNCC, it was was the Central Committee — they spent the better part of the night hassling and hammering, and decided that we could not let the freedom rides be stopped by the violence, that we ourselves were going to take it up and go forward with it.

Diane Nash called me immediately about that decision, and I confirmed it because she wanted to be sure I was on the same wavelength; but I not only said, “Yes, and as soon as I get back I’ll join you; I’ll be there,” but I also said to Diane, “You must call Martin King and Jim Farmer and tell them that we’re gonna take it up. And call Robert Kennedy and tell him we’re gonna take it up.” Because I just knew that’s what had to happen.

So the Nashville movement took it on ourselves to do that. Chances are — and I’ll speculate here — if we hadn’t done that, it would have been quite some time before any major activity took place to ignite the movement again. If the rides had stopped, it would have been seen as a defeat. It would have been off the front pages. Whether or not the Kennedy Administration would have been as forceful in demanding that the Interstate Commerce Commission tell the states and the businesses that segregated interstate travel had to end, I don’t know. [On September 22, 1961, the ICC issued a ruling that outlawed segregation in bus and train stations and airports.]

But I do know we outraged the administration with that behavior. It just astonished them. It also revved up the movement. People all over the country decided they’d participate in the Freedom Rides.

Joan Mulholland’s journal entry from jail:

Washed my hair. Dinner spaghetti with two little chunks of hot dogs & cornbread. Ugh! Ruth can’t take it and has been trying to call the lawyer. Lovely little article in yesterday’s paper about me. Wrote Paul but got it back. He’s bailed out and so has Frank.

This evening we sang a lot. Most girls did folk dancing, but since I’d just washed I didn’t want to get all sweaty. After dinner most of us changed to shorties. I think all the girls in here are gems but I feel more in common with the Negro girls & wish I was locked in with them instead of these atheist Yankees.

The jailer brought by two girls to look at us, including one he brought by last night. The boys have devotions twice a day. Sigh! When I grease up Emmy comes over to have some on her lips. Got paper tonight. Wrote Cecil – smuggled.

Almost as soon as the lights went out the singing started. The boys would sing some, and we’d sing some. A man named Charles (non-rider) has a beautiful voice and sang several solos. Someone further away sang “How Great Thou Art” for Betty. Some white guy kept cursing us out. One guy answered back a little and everyone sang louder. We quit around 11. It was one of the most uplifting experiences I’ve ever had.